Review by John Lombard

When the Miss Behave Gameshow began, the Playhouse audience was cool: receptive to being entertained, perhaps, but wearing the implacable neutrality of good public servants.

An hour later, one audience member was doing a cartwheel in the aisle, another was swinging a sock over his head like a mace, and one more had climbed onto the stage to plant a gentle kiss on the host.

The audience was roused to this frenzy through wicked jokes, a whip-crack pace, and the careful cultivation of an eternal rivalry: the gulf between the privileged few who own iPhones, and the rest of us.

The stage of the Playhouse was converted into an intimate theatre and bar for the show, appropriate for a performance that invited the audience to become part of the spectacle. This impromptu stage was deliberately tawdry with gold glitz, and festooned with crude cardboard signs scrawled with slogans like 'Don’t Ask Don’t Get', 'Life's Not Fair' and 'Black Lives Matter'.

Host Miss Behave (Amy Saunders, a disco-ball of gold sequins) led the audience in an anarchic fusion of game show and cabaret, with phone-themed tribes skirmishing in oddball challenges over non-prizes like a sanitary pad and a ‘Best of Bill Cosby’ record.

Adroit integration of phones with the show had audience members call Miss Behave's personal phone, take speed selfies, and even use phone torches to provide a spotlight.

Miss Behave always kept a heartbeat ahead of the audience, whether pelting it with Mentos, ambushing it with sneaky riddles, or teaching the unfairness of life by granting and stripping points with the zeal of a Hogwarts house master.

The funny and flexible Tiffany was the perfect assistant for Miss Behave, with a formidable high kick matched only by the lance-like points of his moustache.

While dependent on audience participation, the Miss Behave Gameshow did not put people on the spot or embarrass them, but instead gave an open invitation to join in, which most of the audience accepted.

With an ultimate message that victory often goes not to the strong or talented but to the hungry, the Miss Behave Gameshow found an unexpected sweet spot somewhere between cabaret, philosophical treatise, and political manifesto.

The Miss Behave Gameshow is brisk, anarchic fun: the kind of show that is best not as the climax of a night’s entertainment, but a spur to post-show hijinks.

Thursday, January 31, 2019

SINCE ALI DIED

Written and performed by Omar Musa

Directed by Anthea Williams

Presented by The Canberra Theatre Centre in

association with Griffin Theatre Company

Courtyard Studio, Canberra Theatre Centre 30th Jan. to 2nd Feb. 2019

Performance on 30th January reviewed by

Bill Stephens

Having known Omar Musa since he was a very small boy,

lived in the same town, and swum in the same river that inspires much of his

writing, it was a compelling, occasionally confronting, often moving

experience, to listen to his superbly written and stunningly articulated

descriptions of his life growing up in Queanbeyan.

However, you don’t have to have lived in Queanbeyan to

appreciate the forensic accuracy with which Musa describes his observations of

life as a Muslim boy living in a country town where his school playmates tell him

his skin is the colour of shit. Inspired by his response to the death of his hero,

Muhammad Ali, he describes how his best friend, Danny, with a background very

different to his own, introduces him to the temptations a seamy world that

would horrify his devout Muslim father, who insisted that Musa and his mother, join

him in ever-longer daily prayer sessions reading from holy books he could not

understand.

It was these unintelligible prayer sessions, together

with the advice given by his mother as she drove him to school each day, to “question

everything”, that inspired his curiosity and love of words, which he now chooses

with devastating effect to question and describe, in artfully constructed poems

and songs, his responses to the mysteries of life, love and the whole damn

cacophony.

Musa is a charismatic presence. There’s no sign of a chip

on his shoulder as he questions the status quo. His observations are often

brutally frank and sometimes uncomfortable to listen to, but undeniably

recognizable in their truthfulness.

Presented on a bare stage, with excellent backing tapes, moody lighting,

and perhaps a little too loud microphones, his performance sizzles with passion,

humour and curiosity, occasionally vacillating unexpectedly between playfulness

and rage. It’s a performance so compelling that the introduction of a female

back-up singer for a couple of the songs seemed an unwelcome distraction, which

added little except interrupt the carefully achieved rhythm of Anthea Williams

otherwise unobtrusive and thoughtful direction.

This show was recently awarded a Sydney Theatre Award

for “Best Cabaret Production”. That won’t be the last award it receives. Intelligent,

well-written and superbly performed, “Since Ali Died” is also an original and stimulating piece of theatre which should be

seen by anyone interested in questioning their place in an increasingly complex

world.

Photo by Robert Catto

This review also appears in Australian Arts Review. www.artsreview.com.au

SINCE ALI DIED

Directed by Anthea Williams

The Courtyard Theatre,

Canberra Theatre Centre to 2 February

Reviewed by Len Power

30 January 2019

Award-winning author, poet and rapper, Omar bin Musa, hails from

Queanbeyan and is rapidly making a name for himself internationally with his

poetry, novels and music. ‘Since Ali

Died’ recently won a Sydney Theatre Award for best cabaret production.

‘Since Ali Died’ is essentially a one man show with

additional fine vocals by singer, Chanel Cole.

Performed on a bare stage with occasional lighting changes, Omar Musa

presents a very personal mixture of his poems, songs and thoughts.

Musa movingly credits his parents with the strength to

endure and overcome the difficulties of growing up in Queanbeyan as a

brown-skinned Muslim boy. Discovering charismatic

American boxer, Muhammad Ali, gave him a hero to look up to.

Encouraged to question everything happening around him meant

that life probably wasn’t easy, but it gave him a vast store of experiences to

inform his subsequent writing. His show

reflects these life experiences as well as his artistic influences and is a

strong and often confronting showcase for his poetry, words and music.

Particularly effective were his poems concerning his

religion and Malaysian heritage. A lot

of the detail of his growing up in Queanbeyan was disturbing but presented with

wry humour. It was fascinating to hear how

he viewed and coped with experiences at this time in his life, leading to the

development of a unique individuality.

He commands the stage right from the start of his show,

giving a fine performance from start to finish.

There’s a certain amount of larrikin there under the surface with a

wicked smile and a young boy cheekiness which is very engaging. He also shows his clarity of thought about

the world around him, uses the rough language of the tough environment he grew

up in and makes it clear that he has opinions and every right to express them.

There’s no sense of bitterness in his performance. This is a young man who has struggled to find

his place in the world and, through literature and music, shows us with

imagination, humour and determination where he is going.

Len Power’s reviews

are also broadcast in his ‘On Stage’ performing arts radio program on Mondays

and Wednesdays from 3.30pm on Artsound FM 92.7.

Sunday, January 27, 2019

NIGEL KENNEDY - Bach Kennedy Gershwin

Llwellyn Hall – Canberra – 25th January,

2019.

Reviewed by Bill Stephens

It was a hot night, both weather-wise and musically,

and from the moment the audience entered Llwellyn Hall it was clear that this

was not going to be your ordinary concert. Besides the grand piano and five

chairs, there were two yellow lounges Not, it transpired, for the musicians to

sit in, but in which to rest their instruments. Vertical sound bars were

scattered around the stage, with a sound technician tucked in a far corner of

the stage, behind a huge piece of sound equipment.

The band took the stage wearing maroon football

guernseys, with their names embroidered across their backs. Flaunting his

trademark spiky punk-rock hairdo, Kennedy made his entrance wearing similar,

but covered his with a loose jacket set off with grey tracky-dacs and bright

yellow runners. His clothes were the only casual thing about him however, as he

immediately plunged into a mesmerizing rendition of Bach’s “Sonata for Solo

violin No. 1 in G-Minor, BWV 1001”.

Kennedy nominates Bach as his favourite composer, and claims

he uses the Bach solo sonatas as a form of meditational warm-up. This

performance, which he dedicated to Yehudi Menuhin, certainly focused and

transfixed his audience, fascinating them with his complete absorption in, and

mastery of, the intricacies of Bach’s compositional brilliance.

Should he ever become bored with the violin though –as

inconceivable as that might be - Kennedy could forge a second career in

stand-up comedy. His jocular mood, relaxed manner and ever-ready quips, quickly

engaged his audience, as he spoke of his pleasure in performing in Llwellyn

Hall, confiding that both his parents had toured in a trio with Ernest Llwellyn

after whom the hall is named.

He then surprised by sitting at the grand piano and

launching into an un-programmed, gently swinging arrangement of “Arrivedeci

Roma” which he used as a kind of introduction to his accompanying musicians,

guitarists Howard Alden and Rolf Bussalb, Cellist Peter Adams and double

bassist, Piotr Kulakowski, each a virtuoso in their own right.

Kennedy’s obvious respect for these musicians became a

highlight of the performance, as he reveled in challenging them to match his

brilliant improvisations especially with the jazz-inspired Gershwin

arrangements which made up the second part of the program.

But before the Gershwin, Kennedy turned to his “second

favourite composer” for his own composition, “The Magician of Lublin” inspired

by Isaac B. Singer’s book on life in the Shtetls of old Poland. He commenced

this composition using an electronic stringed instrument to conjure up a strange

looping introduction suggesting Klezmer music, before taking to the piano,

where his musicians joined him, to create a series of often dazzling evocations

of characters and events from the book.

Following the sustained applause which greeted this composition,

Kennedy again surprised by previewing the remaining half of the program with a

heavily romantic reading of Gershwin’s “How Long Has This been Going On”.

Kennedy claims to have always hated Gershwin. He

credits Stephane Grappelli to opening his eyes to the pathos, charm, flavor and

craft of Gershwin’s compositions. His virtuosic jazz arrangements of the other

five Gershwin compositions which formed the rest of the concert were real

eye-openers for those in the audience who considered they knew Gershwin.

A cheeky “They Can’t Take That Away from Me”,

sprinkled mischievously with hints of “Strangers In The Night” and “The Harry

Lime Theme”, drew smiles from his colleagues as they responded to his impish

challenges, ending with the longest exit of crashing final chords ever, reducing

the audience to hysterics.

An intriguing combination of “I Loves You Porgy” and “Bess

You is My Woman Now”, from Porgy and Bess” charmed with its lush rippling exit.

Kennedy changed violins for “The Man I Love” featuring ever more complex improvisations,

then a hectic “Oh, Lady Be Good” which featured dueling guitars as, egged on by

Kennedy, Alden and Bussalb challenged each other with ever more complex

improvisations, eliciting cheers from the excited audience.

Of course, there were encores. Kennedy was generous,

offering a rollicking Irish medley combining a jaunty jig and a heartfelt

“Londonderry Air”, then topped if off with a dazzling version of “The Rhapsody

in Blue” entitled “Rhapsody in Claret and Blue” which climaxed with a well-earned

standing ovation in recognition of a memorably joyous evening of superb music

making.

This review also published in Australian Arts Review. www.artsreview.com.au

Saturday, January 26, 2019

THE GRUFFALO'S CHILD

The Gruffalo’s Child.

Adapted from Jennifer Donaldson and Axel Scheffler’s book by Tall Stories.Original director: Olivia Jacobs. Creative Producer: Toby Mitchell. Associate DirectorAustralia/New Zealand Liesel Badorrek. Designer Isla Shaw. Lighting Designer James Whiteside. Puppet designer Yvonne Stone. Choreographer Morag Cross. Associate choreographer: Luanna Priestman. Music and Lyrics: John Fiber and Andy Shaw. Additional lyrics: Olivia Jacobs and Robin Price. Music Production: John Fiber and Andy Shaw for Jolly Good Turnes.Company Stage Manager: Belinda Price. Assistant SStage Manager: Genevieve Davidson. Presented by CDP and Tall Stories. The Q Thjeatre. Queanbeyan and Panarang Council. Saturday January 26th and Sunday January 27th. Bookings 02 62856290 or theq.net.au

Reviewed by Peter Wilkins

In a recent interview, celebrated

children’s author, Jennifer Rowe aka Emily Rodda, remarked on the important

role that children’s literature plays in encouraging the reading habits and

development of young readers into well-rounded adults and lovers of literature.

The same could be said of those who dedicate their art to the adaptation of children’s

books to the stage and write plays for young people of all ages. Nowhere was this more apparent to me than in

the delightful CDP production of Jennifer Donaldson and Axel Scheffler’s popular story,The Gruffalo’s Child. This enchanting stage sequel to The Gruffalo has been directed and

performed with magical flair, entrancing the young audience with excellent

performances, lyrical songs and enthusiastic participation.

|

| Mouse, Fox and Gruffalo's Child |

This stage adaptation pads out

the original story of the Gruffalo’s daughter venturing into the deep dark wood

with physical routines, catchy songs with pertinent morals and audience actions

to keep the young involved and entertained. Rather than a mouse inventing a fierce

Gruffalo to spare it from harm from the snake, the owl and the fox in the

original story, Donaldson’s sequel cleverly inverts the tale to employ the “big

bad mouse” as the threat to strike far into the hearts of her predators.

Heedless of her father’s stern warning and with only a stick to ward off

danger, the Gruffalo’s child eventually comes face to face with the big bad

mouse, conjured up by the wily mouse. The fifty five minute adaptation serves

as a lesson on survival and using wit and imagination to keep out of the way of

harm. Fortunately for Gruffalo’s child, she learns only too well the wisdom of

warning and the importance of heeding sound advice. It is a lesson not unnoticed

by the youngest members of the Q Theatre audience. Like every good story, the

moral is abundantly clear and Gruffalo’s child learns only too well that there

is nowhere as safe as her father’s lap.

| ||

| Madison Hegarty, Jade Paskins and Skyler Ellis |

CDP’s production of Tall Stories’

adaptation is a wonderful theatrical

treat for young and old alike. Performed with sheer enthusiasm, skill and

charming vivacity by three captivating

performers, the production is a

testament to the outstanding qualities of excellent children’s theatre. It is

neither patronizing, nor gratuitous and the actors perform with delight in

their craft and respectful observance of their young audience. Jade Paskins’ Child is deliciously naïve, but

swift to discover her wile. As Narrator and Mouse, Madison Hegarty engages well

with her young audience, although her transition from Narrator to Mouse is less

dynamic. The final moment of the story, when the Gruffalo’s Child returns to

the safety of the father’s lap, seems unresolved. The punch line of the final

episode seems diluted after a series of high octane adventures. It is Skyler

Ellis who impresses with chameleon transitions from narrator to slippery

calypso swivelling snake, professorial owl wheeler-dealing, sly fox and a Gruffalo in

fine voice. His performances are finely honed for their unique personalities.

Liessal Badorrek directs the Australian cast with imaginative flair and

precision on designer Isla Shaw’s simple story book design with art nouveau

shaped trees in front of a full moon. Morag Cross’s choreography is lively and full

of fun and John Fiber and Andy Shaw’s

music and lyrics are simple, catchy and clever, complemented by original

director Olivia Jacobs’ and Robin Price’s additional lyrics.

The tean behind The Gruffalo, Room on the Broom and the various Treehouses of Andy Griffiths and

Terry Denton have scored another magical

triumph with this adaptation of The Gruffalo’s Child, proving that the very

best in Children’s Theatre shares its

place in a nation’s cultural heritage with the very best in adult theatre.

Treat yourself to the magic of The Gruffalo stories as they fill the stage with

colour and delight.

Don’t miss CDP and Tall Stories’

production of The Gruffalo Live on

Stage at The Q from March 27 – March 30

2019

BEWARE OF PITY

Beware of Pity from the novel by Stefan Zweig, in a version by Simon McBurney, James Yeatman, Maja Zade and the ensemble. Schaubühne Berlin, Germany, and Complicité (London), UK. Roslyn Packer Theatre (Sydney Theatre Company), in Sydney Festival, January 23-27, 2019.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

January 23

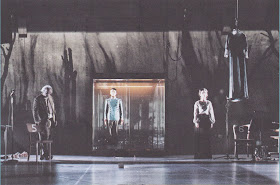

Direction – Simon McBurney; Co-Direction – James Yeatman; Set Design – Anna Fleischle; Costume Design – Holly Waddington; Lighting Design – Paul Anderson; Sound Design – Pete Malkin; Sound Associate – Benjamin Grant; Video Design – Will Duke; Dramaturgy – Maja Zade.

Performers:

Robert Beyer, Marie Burchard, Johannes Flaschberger, Christoph Gawenda, Moritz Gottwald, Laurenz Laufenberg, Eva Meckbach.

If bühne means “stage” and schau means “show”, then an unfortunate English translation of Schaubühne might be a theatre which stages only for show. When I add a translation of Complicité in to the mix, I start to wonder about the motivation for putting on Beware of Pity. Are we expected to be complicit – that is “involved with others in an activity that is unlawful or morally wrong”?

Certainly the style of this production looks terribly like “let’s be as avant garde as possible – that is, ‘favouring or introducing new and experimental ideas and methods’.” That translation’s unfortunate too, since avant garde became old-hat last century.

I actually fell asleep several times during the first hour of this two-and-a-quarter hours with no interval show. At times the story seem to be told by the man I took to be the actual story-teller, yet others who may or may not have been characters in the story – on separate microphones from different places on the basically bare stage – seemed to tell their own story, or somebody else’s; while sometimes it seemed that someone spoke the words of another character who was speaking her words at the same time.

I suppose if Complicité is about turning theatre topsy-turvy for the sake of it, that may not be unlawful. But for me, at least, it looked like show (including lots of sudden explosive noises which woke me up) for the mere sake of show – and that’s pretty much morally wrong theatrically, in my view.

Of course, having to concentrate on reading distant surtitles meant dividing my faculties between watching, listening, working out meaning and keeping up with the storyline – yet it seems that an English company choosing to work with German-speaking actors suggests that this is a planned zeitgeist for many audiences around the world.

However, does the form of presentation mean that the show was completely pointless? Did the interminable story have a theme of note?

What does it mean to beware of the pity expressed by a socially naïve young lower-class soldier, who gets himself into a mess by trying to do the right thing by a young upper-class wealthy partly-paralysed young woman, after innocently asking her to dance? Let’s consider.

In modern times in Australia he would have apologised when he realised the situation, she would have said something like “that’s alright – not your fault.” Her parents might say to him, “Sorry, we should have told you.” Any pity he felt, as any of us might feel, might make us feel a bit guilty and we might say, “Is there anything I can do?”

And yes, it is true that his apparent sympathy for her may turn into warm feelings for him on her part, which he may not be able to reciprocate – and so a complex story might begin. It might even end in her suicide. It might make a two hour movie or even a two-act play (with interval). It might even cause us to think about how an innocent action can lead to unforeseen consequences – a sad reality – but not to Beware of Pity like Shut the Gate with a sign Beware the Dog!

So I’m left seeing this play as being about history, rather than old-fashioned psychology.

Only in the final few minutes, after all those explosive emotional shows, do we get to what may be meant to be the nub of the story. The soldier must obey orders. Archduke Ferdinand of Austria is assassinated, the soldier must leave with no way to communicate with the distraught young woman. She kills herself; he faces the other kinds of explosions but survives World War I; his uniform ends up in a museum. In 1939 (the year when “The great Austrian writer Stefan Zweig [who] was a master anatomist of the deceitful heart” according to Goodreads, published his only novel) he tells his story to visitors seeing his uniform – and in some way this may be meant to be a warning about the foreboding World War II, when soldiers must again obey the Führer, whatever the consequences. And was the young woman Jewish? That might make sense.

Or that may be just my imagination. If I’m right, the production of Beware of Pity has some point. If not, it seems an odd play to present about such out-of-date attitudes and understanding of psychology – even for Jung or Freud.

So be a bit wary of Beware of Pity – you’ll need an open mind, but be ready to close your ears unpredictably while watching the surtitles like a hawk.

|

| Photos by Will Duke |

MAN WITH THE IRON NECK

Man with the Iron Neck by Ursula Yovich, based on an original work by Josh Bond. Legs on the Wall, in Sydney Festival at Sydney Opera House, Drama Theatre, January 23-26, 2019.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

January 24

Photos by Victor Frankowski

|

| Tibian Wyles, Kyle Shilling, Caleena Sansbury as Ash, Bear and Evelyn |

|

| in Man with the Iron Neck Legs on the Wall |

Co-Director and Original Concept – Josh Bond; Co-Director – Gavin Robins;

Writer – Ursula Yovich;

Co-Composers – Iain Grandage and Steve Francis; Set Design – Joey Ruigrok;

AV Design – Sam James; Lighting Design – Matt Marshall; Costume Design – Emma Vine; Sound Design – Michael Toisuta and Jed Silver; Dramaturg – Steve Rodgers.

Performers:

Ursula Yovich – Mum Rose

Kyle Shilling – Bear

Tibian Wyles – Ash

Caleena Sansbury – Evelyn

|

| Kyle Shilling in Man with the Iron Neck |

|

| Ursula Yovich, Tibian Wyles, Kyle Shilling in Man with the Iron Neck |

The purpose for creating Man with the Iron Neck is clear and important. Why do people commit suicide? Why young people? Why young Indigenous people in particular? Why this particular Indigenous young man, nicknamed Bear by his twin sister Evelyn?

Before the story telling began – by Evelyn’s boyfriend, aspiring actor Ash – the welcome to Gadigal land, on which the Sydney Opera House stands, included a minute’s silence in which the audience stood in memory of the nine Australian Indigenous girls, aged 15, 14 and 12, who have taken their own lives just since the beginning of this year – that is in the first 24 days.

Bear’s fictional story represents all that tragic truth.

Ash begins with his story of The Man with the Iron Neck, which you can find at https://www.oldtimestrongman.com/blog/2018/02/01/great-peters-man-iron-neck/ . Posted on Thursday, February 1st, 2018 by John Wood: “Aloys Peters was a German acrobat who developed an unusual skill — he could jump off a platform 75 feet in the air with a hangman’s noose around his neck and yet not hang himself. He had figured out the knack where he could maneuver his body mid-air and “tame the arc” taking the jolt out of gravity’s cruel grasp. Peters performed this feat initially for the famous Strassburger Circus in Berlin and then the Sells-Floto Circus on US shores in the early 1930’s.”

From this image, Legs on the Wall – a company famous for aerial dance – turn Rose’s teenage children into literally flights of fantasy, firstly swinging on the rotating Hills Hoist clothesline, which itself takes off in a dangerous entanglement, and jumping from the high limbs of a giant eucalypt, culminating in the hanging – when Ash, Evelyn and Rose herself cannot lift Bear’s body to save his broken neck.

|

| Kyle Shilling as Bear in Man with the Iron Neck |

|

| Caleena Sansbury and Tibian Wyles as Evelyn and Ash in Man with the Iron Neck |

|

| Ursula Yovich as Mum Rose in Man with the Iron Neck |

But it is not the physicality, the mental visualisations or the emotional anguish of Bear’s sister, his friend, nor even of his mother, which ask the key question. Why did he do it?

The answer is shame. Bear rarely spoke. He was a young man of action, an AFL footballer who had won his first professional placing – only to have a racist call him a ‘monkey’. This had happened in reality to Adam Goodes: [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Goodes ]. Bear was ashamed because he could not restrain his feelings, punching in response, sending his attacker to hospital with a broken nose. Should he have walked away, maintaining his dignity?

But suicide…? Not only because he had broken the code of responsible behaviour the football team expected, but because he – and we – realise that racism is the lot of Indigenous people daily throughout their lives. This is what makes life not worth living.

So, the story is powerful and needs to be told. Does the theatrical presentation stand up? Not so well, in my view.

The dialogue, the choreography and the imagery tell the story too literally. Legs on the Wall in previous work has moved and created images more poetically, making our imaginations work to seek out their meaning.

In the scriptwriting, when Mum Rose expresses her feelings in a soliloquy, and when Ash makes his final observations about Bear and Evelyn, we are drawn in to identifying and deeply empathising with them. Ursula Yovich especially stood out in her performance at this level. But the characters of the young people, aged 16, needed much more development, with less obvious words and actions. We needed to know from the beginning there were complex unexplainable feelings in the family and friendship relationships. For this, though the words spoken might seem ordinary, the implications in the spaces between words must raise questions in our minds about what Mum Rose, Evelyn, Ash and Bear are really thinking and feeling about each other and themselves.

Then, with poetry in the aerial motion, Man with the Iron Neck could become the greater theatre experience which the importance of its theme deserves.

_________________________________________________________________

Following this short season at the Sydney Festival,

Man with the Iron Neck will be at the Adelaide Festival

Fri 8 March – Mon 11 March, 2019

Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre

https://www.adelaidefestival.com.au/events/man-with-the-iron-neck/

while another Sydney Festival show, Counting and Cracking, reviewed here Sunday January 20, will be on March 2 – March 9, 2019, at the Ridley Centre, Adelaide Showgrounds, Goodwood Road, Wayville, Adelaide. Tickets & Info: https://www.adelaidefestival.com.au/events/counting-and-cracking/

Friday, January 25, 2019

PIGALLE

|

| "Pigalle" in the Magic Mirrors Spiegletent - 2019 Sydney Festival |

Produced by Peter Rix - Directed by Craig Ilott

Musical Direction by Joe Accaria - Choreographed by

Lucas Newland

Wardrobe designed by James Browne - Lighting designed

by Matt Marshall.

Magic Mirrors Spiegletent – Hyde Park – 8 – 27th

January

Performance on 12th January 2019 reviewed

by Bill Stephens

|

| Marcia Hines in "Pigalle" |

Disco Circus Fusion, especially the Spiegletent

variety, has become a staple at festivals around Australia. Director Craig Ilot

has mastered the genre with a succession of boundary pushing, crowd-pleasing

productions which include the mesmerizing “Smoke & Mirrors” and “Velvet”. “Pigalle” is a variation on both these shows,

and while highly entertaining, lacks the originality of concept which made

these shows memorable.

Ilot has assembled a first class cast of singers,

dancers and acrobats, costumed them in eye-popping costumes, added brilliant

lighting design, masses of mirror balls, head-banging disco music, obligatory fog,

some weird characters to provide mystery, and woven them into a clever but strangely

confusing format which reflected little of the Parisian ambiance suggested by

the title, “Pigalle”.

As the audience entered the magnificent Magic Mirrors

Spiegletent and scuffled for the best seats, it was entertained by loud disco

music provided by a pretty young female disc-jockey earnestly twiddling knobs

on disco equipment artfully arranged centre stage on garbage tins and wooden

fruit boxes.

As soon as the last of the audience had found seats, the

disco equipment was dispensed with and the full cast, including legendary disco

diva, Marcia Hines, was introduced to a well-choreographed version of Randy Crawford’s

“Street Lights”. Then in a riot of dazzling lights and pumped up sound, a

series of brilliant specialty acts followed, each more jaw-dropping than the

last.

|

| Iota with Yammel Rodrigues and Hugo Desmarais |

Aerial artists Yammel Rodriguez and Hugo Desmarais

drew gasps, both as soloists and together, with their intricate, high-risk

routines performed on various apparatus high above the audience.

|

| Katherine Louise McLaughln in "Pigalle" |

Cheeky Katherine Louise McLaughlin (Aka “Kitty Bang

Bang”) could hardly wait to demonstrate how prettily she could shed her

gorgeous costumes. She later surprised even more, with an astonishing

fire-eating act which took tassel-twirling to a fiery new level. Violinist

Sonja Schebeck charmed with her musical talents before revealing her own

unsuspected fire-eating talents while assisting McLaughlin.

|

| Zachary Webster - Marcia Hines - Chaska Halliday in "Pigalle" |

Easy-on-the-eye singer/dancers, Chaska Halliday and

Zachary Webster, were much more than eye-candy. They changed costumes endlessly,

tossed off Lucas Newland’s tricky choreography effortlessly, and provided classy

backup singing for the legendary, Marcia Hines, who has never looked more

relaxed and happy, belting out a succession of disco songs with the same

undimmed pizzazz and authority that earned her the accolade of “Queen of Pop”

more than 40 years ago.

And on the subject of pizzazz, white-faced,

velvet-voiced, Iota was the icing on the cake as he prowled the stage,

outrageously costumed and obviously relishing the company and environment.

It was an imaginative move to include for Bangarra

dancer, Waangenga Blanco, in the show. But it appeared that having cast him, Ilott didn’t know what to do with him. So

charismatic in Bangarra Dance productions, in this show, dressed in street

clothes in contrast to everyone else’s disco glitter, his idiosyncratic movement style, deprived of

point and purpose, quickly became repetitive, even boring. Pity, because in the

finale, costumed in a natty velvet suit, he suddenly came to life.

Images: Prudence Upton