“Canberra Citynews”

Artist of the Year

Dianne Fogwell

One of Australia’s most revered print artists has been named 2021 “Canberra Citynews” Artist of the Year at the 31st annual ACT Arts Awards evening, held in the Canberra Museum & Gallery on Tuesday evening 30 November.

Dianne Fogwell was singled out for an extraordinary year of work, but also for a lifetime of technical mastery of her art, combined with an Alice in Wonderland-like imagination that defies pigeonholing.

|

| From Left: Ian Meikle, Dianne Fogwell, Minister Cheyne, Meredith Hinchcliffe |

The ACT Minister for the Arts, Ms Tara Cheyne MLA, presented

her with a certificate and “Citynews” editor, Ian Meikle, presented her with a cheque

to the value of $1,000. Craft writer,

Meredith Hinchliffe, gave her a finely-crafted stainless steel bowl from F!nk studio.

Fogwell said she was delighted to receive the award adding, “Canberra‘s got a lot to be proud of, where a city of creative people…if we don’t take ourselves seriously who else is going to do it?”

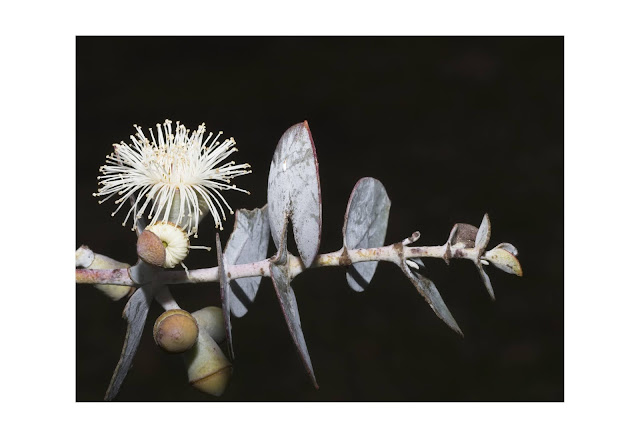

Praised by critics as the creator of dream-like realities set within a specific Canberra “wonderscape,” she was single out for her exhibition, “Transient,” at Beaver Galleries in November 2020, which captured the eerie light cast by the blanket of smoke and unburnt particles over Canberra during the 2019 bushfires.

Fogwell is embedded in the history of Canberra’s visual arts, she was the co-founder of Studio One print workshop, founder/director of the Criterion Press and Fine Art Gallery and a long-time lecturer in printmaking, graphic Investigation and lecturer in charge of the Edition + Artists Book Studio at ANU School of Art.

She is also known as a master printer who has editioned prints professionally for prominent Australian artists, including Jason Benjamin, Margaret Olley and Robin Wallace-Crabbe, while maintaining her own art practice.

She has won the Megalo International Print Prize and the Australian Artists’ Book Prize and was recently announced as the winner of the 2021 Geelong Acquisitive Print Awards.

In a busy year, she was an invited artists in the 11th Triennial of Chamalieres in France, won an award of excellence in the inaugural WAMA Art Prize for works on paper in in the Grampians, and was commissioned to complete a 45-meter installation for the Geelong Art Gallery.

Fogwell has been an exhibiting artist since 1979 and has been an invited artist to international biennials for print and the artist book as far afield as Poland, Belgium, Belgrade, France, London and Korea.

Her work is represented in the National Gallery of Australia, Art Bank, the Australian War Memorial, the Chicago Institute of the Arts, The National Museum for Women in the Arts in Washington DC and the China Printmaking Museum in Shenzhen.

Helen Tsongas Award for Excellence in Acting

Dylan Van Den Berg

Earlier in the evening, an exceptional Canberra actor-playwright was presented with the Helen Tsongas Award for excellence in acting by Canberra Theatre director, Alex Budd.

Dylan Van Den Berg was singled out by the Canberra Critics Circle for a remarkable year of acting and writing, especially in his play “Milk,” presented at The Street Theatre in June, in which he played a character with a background very much like his own.

“I am incredibly honoured to receive an award in Helen’s memory…awards like this are immensely encouraging for artists and it is a real privilege,” Van Den Berg said on learning of the decision.

|

| Dylan Van Den Berg |

In April this year he had also won the $30,000 Nick Enright Prize for Playwriting for “Milk” at the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards.

A Palawa writer/performer with family connections to the Bass Strait Islands and the northeast of Tasmania, Van Den Berg is now a full-time theatre artist, but until recently worked as Inclusion & Diversity Advisor at Starlight Children's Foundation Australia and before that as performance expert and Captain Starlight recruiter.

The multi-talented Van Den Berg has a BA in Drama and international Communication from the ANU and a diploma in Indonesian from the University of New England, as well as qualifications improvisation at the State University of New York.

Very much a product of The Street Theatre, where he has performed as a professional actor many times, he came to public attention there in 2019 as Gregor Samsa in Kafka's “Metamorphosis,” who turned into an insect.

He also had his plays like “Blue: a misery play” and “The Camel” developed under the theatre’s dramaturgical programs, The Hive and First Seen.

In 2021 critics praised both the gentle restraint of his performance as a younger generation indigenous man and the play, described by the “Citynews” reviewer Joe Woodward as “a matter of cultural necessity.”

In meeting the challenge of playing himself in “Milk,” he has said he objectified the part, declaring, “just the fact that I wrote it means I removed it from myself”.

Van Den Berg has said that he wrote the play for his baby daughter, Charlotte, to whom he said: “I wrote this play for you and you’ll know where we come from.”

The Helen Tsongas Award for excellence in acting was established by the Tsongas family in the name of the late Helen Tsongas, who died in a motorcycle accident with her husband, Peter Brajkovic, ten years ago.

|

| The late Helen Tsongas |

Tsongas was a dramatic actor, memorable for tragic roles in “Medea” and “The House of Bernarda Alba” but equally admired for her comic roles in plays like “Noises Off” and The Female Odd Couple”

She worked at Arts ACT for many years (former Chief Minister Jon Stanhope was, at the time, the Arts Minister) and then moved to the then Commonwealth Office for the Arts when Simon Crean was Minister for the Arts.

She would have been 43 in November this year.

The Helen Tsongas award takes the form of a cheque to the value of $1000 and a certificate going to the best Canberra actor of the year, with no restrictions on age or gender, as judged by the theatre panel of the Canberra Critics Circle and will continue over the coming years.

The 2021 Canberra Critics Circle is as follows:

Canberra Critics Circle Awards

The centrepiece of the 31th ACT Arts Awards was the presentation of Canberra Critics Circle certificates by Patrick McIntyre, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the National Film And Sound Archive, to the artists below:

Theatre

For her evocative lighting design, an intuitive and expert complement to the visceral impact of music, dance and soundscape in Belco Arts’ production of MESS.

Theatre

Dylan Van Den Berg

For his deceptively gentle and restrained performance in and writing of Milk, a play that works on many levels. This immersive, haunting piece has been shaped so well that it becomes a memorable experience that stays with an audience long after it has finished. A Street Theatre production.

Theatre

Musical Theatre

Musical Theatre

Helen McFarlane

For her exuberant portrayal of the worldly, sophisticated friend, Tanya, a role which demanded mastery of triple-threat skills in Free-Rain Theatre’s production of Mamma Mia.

Photography

Melita Dahl

Opening a new chapter in the art history of portraiture, deadpan and deliberate facial distortions become political statements in her technically excellent exploration of avenues to subvert facial recognition and facial emotional recognition technologies. For her exhibition Portrait at PhotoAccess.

Photography

Sammy Hawker

Walking on Yuin, Ngarigo, and Ngunnawal Countries, then processing with collected water, soil, bark and flowers, employing pigment inks, emulsions and silver nitrate to create prints humming with the presence of the sites; unsettling and thrilling. For her exhibition Acts of Co-Creation at Mixing Room.

Visual Arts

Stephen Harrison

For his sculptures, drawings and paintings that encompassed a strong, dark vision of humanity but also offered a beacon of light. For his exhibition, You want it darker at Belco Arts Centre in March 2021.

Visual Arts

Sharon Peoples

For her innovative and beautiful use of embroidery to illustrate the theme of our relationship to nature and our cultivation of the garden, culminating in her exhibition Between Earth and Sky at CraftACT in May 2021.

Visual Arts

Janet DeBoos and Wendy Teakel

Two senior artists found deep veins of shared philosophy, awareness and understanding in their appreciation of the landscape. For their moving exhibition Intersections at Craft ACT in February 2021.

Visual Arts

For her beautiful and important print exhibition, which showed her experience of the 2019 bushfires in Canberra. She captured the eerie light cast by the blanket of smoke and unburnt particles over Canberra. For her exhibition Transient at Beaver Galleries in November 2020.

Music

Dan Walker

For his conducting of the Oriana Chorale in the performance of Text/ure in collaboration with Canberra poet, Sarah Rice, in which his music, “If I could have given you a note”, was performed and for the 11 concerts he performed in and led over the last year, including in the Canberra International Music Festival.

Music

Phoenix Collective, led by Dan Russell

For their mesmerising and entertaining exploration, led by Dan Russell, of the music of the tango from its earliest days right up to the “nuevo tango” styles of Astor Piazzolla and living up to their own motto to perform “concerts that excite & inspire.”

Music

Christopher Latham

For Vietnam Requiem, an epic concert of three hours, engaging all the senses, employing vast music forces of varying music genres and cultures, and performing a suite compiled of works by Australian composers in a moving commemoration of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

Music

Rowan Harvey-Martin

For her work for and in the first concert by Anomaly, a new ensemble devoted to lesser-known choral works, in which they performed Passion Music by William Todd, a work for choir, soprano soloist and jazz band.

Music

Canberra Symphony Orchestra Chamber Players, led by Kirsten Williams.

For capturing the sublime and distinctive harmonic structure and beauty of melody, harmony and balance in the Phantasy Quintet by Ralph Vaughan Williams, combined with living every note and nuance of Brahms' String Quartet No.2 in G” in a vibrant, exuberant and joyful performance led by Kirsten Williams.

Music

Wayne Kelly

For leading his jazz trio in a performance of Thelonious Monk’s music, with a nod to

Chick Corea, as well as profoundly personal originals, one

of which, a suite of four parts, acknowledged the topsy-turvy year of 2020 and

his deepening religious faith, all showcasing his unique piano stylings.

Dance

Bonnie Neate and Suzie Piani

For their remarkable re-imagining of Giselle, which they produced, directed and choreographed embracing elements of classical ballet, contemporary and commercial dance, to create Unveiled, a thrilling evening of impeccably prepared, presented and performed dance to showcase the talents of twenty pre-professional dancers chosen at open audition.

For her imaginative, exuberant and brilliantly crafted choreography for Free Rain Theatre’s production of Mamma Mia.

Film

Deborah Kingsland and Hannah de Feyter

For their inventive adaptation to a changing market and a changing audience and their needs through the film festival Stronger Than Fiction, including offering childcare to patrons.

Writing

Lucy Neave

For Believe in Me, (UQ Press, August 2021) a complex and wise novel in which a young woman pieces together her mother’s life story, hoping to understand her better and come to terms with her own history and identity.

Writing

Irma Gold

For the novel The Breaking, (Midnight Sun, March 2021) a confronting story of the link between animal tourism and cruelty in the elephant camps of Thailand, seen through the eyes of two young women.

Writing

Merlinda Bobis

For The Kindness of Birds (Spinifex, May 2021), a poignant collection of linked stories that travel between Canberra and The Philippines to pay homage to kindness amidst grief, discord and displacement, using the metaphor of birds.

Writing

Sarah Rice

For Text/ure (Recent Work Press, 2021) a full colour book, a feast for eye and ear alike, that follows the author-artist as she commissioned original music from six Canberra-connected composers based on her poem, “If I Could Have Given You A Note,” which were later performed by the Oriana Chorale, backed by her own projected artworks.

Awards Presentation Photos by Len Power