Tuesday, November 17, 2015

My Zinc Bed by David Hare

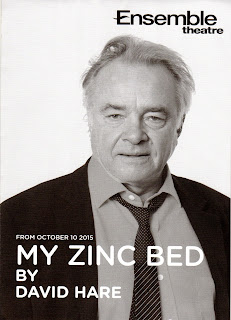

My Zinc Bed by David Hare. Ensemble Theatre, Sydney, directed by Mark Kilmurry. Designer – Tobhiyah Stone Feller; Lighting – Nicholas Higgins; Wardrobe – Alana Canceri; Make-up – Peggy Carter. October 10 – November 22, 2015.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

November 14

It’s not clear to me why Victor Quinn (one-time British Communist, but nowadays – in the year 2000 – a wealthy financier) refers to his death bed as his ‘zinc’ bed. Maybe it’s a reference to commodity prices: if the price of zinc falls, he is ‘dead’.

But the deathly pallor of the metal might be an image of the mortuary bench on which Quinn would have been laid out after his car crash. Suicide? Very likely.

Especially since the play is horribly prescient of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

It’s easy to focus on the superficial question posed by Paul (poet – but only when he’s drunk) and Victor’s wife Elsa, already with two children and ruined by alcohol and drugs when he, Victor, rescued her from the floor of a bar in Denmark. Is it really true that alcoholism is a disease which can be managed or cured – by Alcoholics Anonymous – or is this obsession built into some people’s genetic structure?

Many others over its fifteen year life thought that was what the play is about, but I saw David Hare using alcoholism as just one example of obsessive human behaviour. Others in this play are sexual lust – or falling in love – and power, which Victor epitomises, whether as Communist or financier, employer (of Paul) or husband. He crashes when can no longer believe he is in control of any of these things – even including alcohol, five times over the legal driving limit in his bloodstream.

Not a very happy play, but Mark Kilmurry succeeds in making clear to his audience (and we do listen to a lot of talk) what is actually going on in the feelings of each character.

Danielle Carter plays Elsa Quinn with an awareness of her previous degradation, reliance on Victor and attraction for Paul which leaves us wishing she could do more than outwardly present the calmness and dignity she knows she needs for the sake of her children.

Sam O’Sullivan as Paul Peplow is physically almost as floppy as he is indeterminate mentally while maintaining AA rules; but when he drinks he becomes the sexual being, and poet, that Elsa can’t resist.

Sean Taylor as Victor is made up and dressed in absolute contrast to Paul’s pale and wan poet. He has the presence and voice of authority about him – yet every now and then he senses his own insecurity. Like when he makes and drinks a margarita or three.

However unhappy the play, this production is satisfying theatre. This cast and this director have found the trick of David Hare’s writing, so that we both appreciate and even empathise with each character equally, and yet remain at just enough distance to see each in a clear objective light.

And in doing so, we see Hare’s purpose: to show how our natural human tendencies lead us, sometimes, into ineffable difficulties – in our personal lives as we interact with the world at large. We need more than a version of Alcoholics Anonymous to save ourselves from a Global Financial Crisis. Revelatory group meetings in a circle can become addictive, but can they permanently solve our behavioural contradictions?

This a worthwhile production of a significant play.