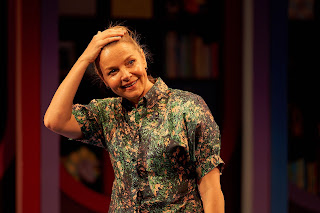

Justine Clarke in Girls and Boys

Girls and Boys by Dennis Kelly.

Directed by Mitchell Butel.

Performed by Justine Clarke.Designed by Ailsa Paterson. Lighting

designer Nigel Levings. Sound designer. Andrew Howard. Accent coach Jennifer

White. State Theatre Company South

Australia in association with Adelaide Festival. Odeon Theatre, February 25 –

March 12 2022.

To say that Justine Clarke’s performance in Dennis Kelly’s

play Girls and Boys is magnificent would be an understatement. Clarke’s

character is named Woman in the programme. She is in fact all women. We meet a

bright, funny carefree woman who has decided to resign her mundane job, shake

off the shackles of routine and

expectation and spread her wings and

explore the world and a new life. Clarke’s entire persona suggest a bubbly,

cheeky, fun-loving woman. With girlish glee she recounts her liberation, her

joyful sexual experiences and her observances of two models who attempted to

jump the queue at the airport by using their guile to persuade a man to let

them in, only to be unexpectedly rejected by a man who cleverly exposed their

deceitfulness. Not everything is as it seems. Kelly’s writing is sharp, witty and lively.

Clarke inhabits the character entirely, sweeping the audience along with her

vitality and wicked humour. Alone on

the stage, Clarke addresses her audience directly, delivering lines to members

that she sees before moving on to somebody else. Each person becomes drawn into

her story, captivated by her energy and natural performance. Her vivacious

narrative is complemented by director Mitchell Butel’s carefully and sensitively

orchestrated direction and Ailsa Paterson’s

pink and blue contemporary setting framed by arches behind which are

small cubicles of boxes, lights and props. It resembles a toy emporium, lending

a bright aspect of affluence and playful imagination. At the outset, playwright

Kelly and the production team of State

Theatre South Australia lure the audience into a false sense of expectation.

The woman’s story becomes more familiar as she marries the

love of her life and has two children , Leanne and Danny. As a result of her honesty and

forthright personality she is successful

in getting a job with a documentary film development agency. Her life is

complete. Her future secured. Clarke’s performance glows with contentment. We

don’t see the children. Clarke mimes her

interaction and addresses the empty space where her children are and plays

games with them, sorts out their arguments and maintains at all times the

natural world of a wife and mother.

“They are not really there” the Woman says. Kelly’s writing

is precise, his dialogue direct and utterly believable in Clarke’s brilliant

delivery, There is a sense of pain in the delivery, which passes momentarily

until her story takes its horrifying turn and bit by bit this lively, joyful,

loving woman’s life begins to fall apart.

Pleasure turns to pain in the telling of events that lead to the final

unimaginable act. The use of mime begins to make sense as memory directs

Clarke’s performance. A mother’s panic when a child goes missing in a crowded

shopping centre; the games and playful interaction with young children; the

moment of motherly love as the children lie with her. Memory becomes the messenger

of comfort and of grief.

Clarke runs the gamut of emotion in a performance that is not only so believable that we feel that we are travelling her memories with her, but is forcibly etched upon our memory long after we leave the theatre. Every detail of the breakdown in the relationship is contrasted with the woman’s success in a documentary film business she has developed with her former colleague Liam. Is it this that led to the horrific crime? Is it the failing furniture business that caused her husband to carry out the heinous crime.

We feel the woman’s pain. We share her grief. Clarke takes

her audience beyond the role of passive observer. Her performance, so visceral

and powerful demands attention. The

performance comes to a close with Clarke directly addressing the audience as

though at a conference to highlight the probable causes of what is termed

Family Annihilation and the overwhelming role of men as perpetrators. These are

not didactic statistics. These are the facts that have ruined the Woman’s life.

These are the circumstances that give Clarke’s performance under Butel’s

direction meaning.

Girls and Boys is

confronting theatre that needs to be seen and a story that needs to be told and

acted on. It does not provide simple solutions but it does inform and encourage

change in a society established to protect such victims. If theatre has the

power to change then the State Theatre’s production of Girls and Boys will undoubtedly be the most important and

theatrically powerful production in its repertoire.