An autobiography by

Leanne Benjamin with Sarah Crompton.

Published by Melbourne Books.

Reviewed by Bill Stephens OAM

Life is full of co-incidences, and the release of this

book in this particular month is one of the happy ones. In early November 2001,

I was passing through London on my way home from attending the New York Cabaret

Convention and reviewing the premiere by American Ballet Theatre of Stanton

Welch’s ballet Clear. Arriving in

London, I discovered that Australian ballerina, Leanne Benjamin, was

programmed to dance the lead in the Nureyev version of Don Quixote. Newly appointed Artistic Director of the Royal

Ballet, Ross Stretton, had arranged to borrow the Australian Ballet’s sets and

costumes, and for this performance Benjamin would be partnered by Cuban dancer,

Carlos Acosta.

Never having seen Benjamin dance, but certainly aware of

her from the reviews of her performances, the opportunity to actually see her

dance, particularly with Acosta, was irresistible. I was also interested to see

how the Australian production, with which I was familiar, would work on the

Royal Ballet dancers, and of course there was the added lure of being able to experience

the newly refurbished Royal Opera House.

Though the performance was sold out, I managed to secure a ‘standing room' ticket to

stand at the back of the Royal Opera House stalls. However my excitement was somewhat

dampened on arrival by a notice advising that Miss Benjamin was indisposed and her

role as Kitri would be danced by Romanian ballerina, Alina Cojocaru. So I never

got to see Leanne Benjamin dance.

Although I never did get to see her dance, having just

read Benjamin’s captivating account of her career, which she’s written with dance critic and arts

editor Sarah Crompton, I feel I’ve finally caught up with her, and even

discovered the reason for her absence on that particular night in November 2001.

“Leanne Benjamin: Built for Ballet” is a fascinating

no-nonsense account of the ups and downs of the life of a career dancer. In

addition to her undoubted brilliance as a dancer, Benjamin reveals a talent for

self-examination, able to assess her own and her colleagues particular talents

and flaws with admiral clarity and perception.

Her knack of being able to verbalize her feelings, particularly with regards to her reasoning for some of the difficult decisions she’s had to make during her long career make fascinating reading. Her advice for coping with the challenges of constant touring and her descriptions of what she has learned from the many dance luminaries with whom she has created and danced should be required reading for any young person contemplating a career as a professional dancer.

Born in Rockhampton, Leanne Benjamin, OBE, AM, is not as well known to Australian dance audiences as her illustrious career suggests she should be. That’s because most of her career has been overseas.

Benjamin was only 3 years old when she commenced her dance

training in Rockhampton, Queensland. By

the time she was 15 she had been accepted into the Royal Ballet School in

London. Her sister, Madonna was already dancing in the corps de ballet of the

Royal Ballet when 16 year old Benjamin travelled to London to take up her place

in the Royal Ballet School.

She quickly realised that she was never going to fit the

traditional mould as a classical ballerina. Her sights were set on becoming a

dramatic dancer. Nevertheless, following considerable success in International

ballet competitions, by the time she was 18 she was dancing in the corps de

ballet of the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet.

The Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, later to become

Birmingham Royal Ballet, at the time Benjamin joined, was the touring arm of

the Royal Ballet, and Benjamin’s athleticism and sense of the dramatic soon

attracted attention. By the time she was 22, following her debut in Swan Lake, she was promoted to Principal.

Her descriptions of touring with Sadler’s

Wells Royal Ballet are insightful and vivid, especially her recollections of performing

Giselle in a circus tent during a

heavy rainstorm.

|

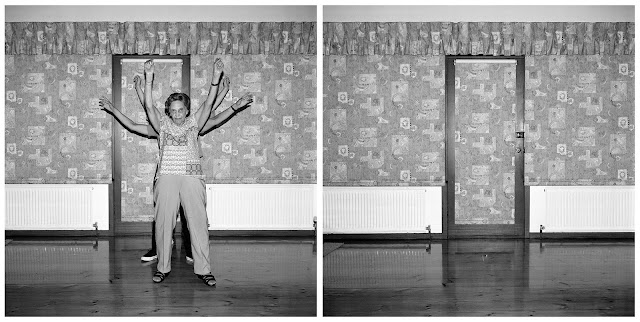

| Narelle Benjamin and Stephen McRae in Kenneth MacMillan's "Manon". Photo:Johan Persson |

Initially attracted to the idea of dancing in America, the opportunity to dance more of the Kenneth MacMillan repertoire led to her decision to join the Royal Ballet in 1992. At the time Sylvie Guillem, Darcey Bussell and Viviana Durante were the reigning ballerinas. Ambitious, energetic and not afraid to speak her mind, Benjamin initially felt stifled by the rigid systems in place.

Choreographer Peter Wright described her as ‘the most

difficult ballerina when it came to rehearsals, demanding time in the studio

and on stage upsetting everybody’. She remembers Administrative Director of the

Royal Opera House, Anthony Russell- Roberts, telling her in no uncertain terms when

she was negotiating for more recognition, that if she wanted to stay at the

Royal Ballet, she would have to accept that she would never be prioritised

before Sylvie, Darcey and Viviana. Nevertheless, by the time she retired from the

stage at age 49, she had been a principal ballerina at the Royal Ballet for

more than 20 years.

Though she danced her share of ballet princesses, it was the story-telling aspects of the big traditional ballets that most interested her, particularly those choreographed by Kenneth MacMillan. She also revelled in the challenges offered by young emerging choreographers, and following early success creating the role of Grete in David Bintley’s Metamorphosis, went on to cement her reputation in works highlighting her unique athletic and dramatic gifts especially Wayne McGregor’s Qualia and Kenneth MacMillan’s Different Drummer and The Judas Tree.

|

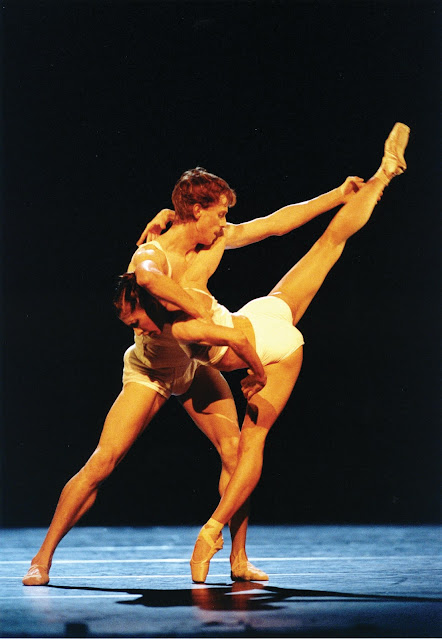

| Narelle Benjamin and Edward Watson in Wayne McGregor's "Qualia". Photo: Bill Cooper |

Benjamin commenced her ballet career during a golden

period of British ballet, a time when the creators of some of the most iconic

ballets in the current repertoire were still practicing. Frederick Ashton coached her for a revival of

his version of Romeo and Juliet, and Kenneth

MacMillan coached her for his. She much

preferred the MacMillan version. Their

admiration for each other’s talents was mutual and MacMillan became her mentor

and lifelong friend. It was a MacMillan ballet, Mayerling that she chose for her final performance at the Royal

Opera House in 2013. Her description of this event is particularly poignant.

MacMillan was not her only influence however. As is the

tradition in ballet Benjamin was taught many of her roles by the dancers who

had originated them. Antoinette Sibley taught her Ashton’s The Dream. Natalia Makarova taught her La Bayadere. Lynn Seymour coached her for McMillan’s Anastasia. Galina Samsova coached her

for Swan Lake; Suzanne Farrell

coached her for Balanchine’s Symphony in C.

For Firebird her coach was Monica Mason, who was taught the role by Margot

Fonteyn, who in turn had been taught by Tamara Karsavina on whom the ballet had

been created by Mikhail Fokine. Benjamin’s accounts of these coaching sessions

are illuminating. Since her retirement Benjamin herself has become much

sought-after coach.

Benjamin speaks glowingly of her stints guesting with the

Australian Ballet under David McAllister’s directorship. She’s rather less effusive

when talking of Ross Stretton who, when he was Artistic Director of The

Australian Ballet and she was contemplating returning to Australia, refused to

engage her as a principal. They appear to have forged an amicable working

relationship later when he took over Artistic Directorship of the Royal Ballet.

Her list of dance partners during her career reads like a

Who’s Who of male dancers. Jonathan Cope, Jose Carreno, Nigel Burley, Ethan

Stiefel, Angel Corella, Carlos Acosta, Steven McRae and Irek Mukhamedov were

all favourites. But it is Edward Watson who she credits as being her perfect

match as a dance partner, able to challenge and compliment her in temperament,

athleticism and artistry.

|

Leanne Benjamin and Edward Watson in Kenneth MacMillians' "The Judas Tree". Photo:Royal Opera House. |

Far from a simply being a list of her triumphs, though there a plenty of those, “Leanne Benjamin: Built for Dance” captures Benjamin’s thoughts on many topics, including coping with injuries and touring, the importance of strong family connections, and her marriage to theatre executive Tobias Round. She’s convinced that her best dancing was achieved in the ten years following the resumption of her career following birth of their son, Thomas.

Fortunately many of her performances are preserved on YouTube

and DVD, and to be able to dive into them while reading her accounts of their

creation added greatly to the pleasure of reading this book which I found difficult

to put down once I commenced reading it.

This review also published in AUSTRALIAN ARTS REVIEW . www.artsreview.com.au

"Leanne Benjamin - Built for Dance" - Available from Melbournebooks.com.au