Book Review

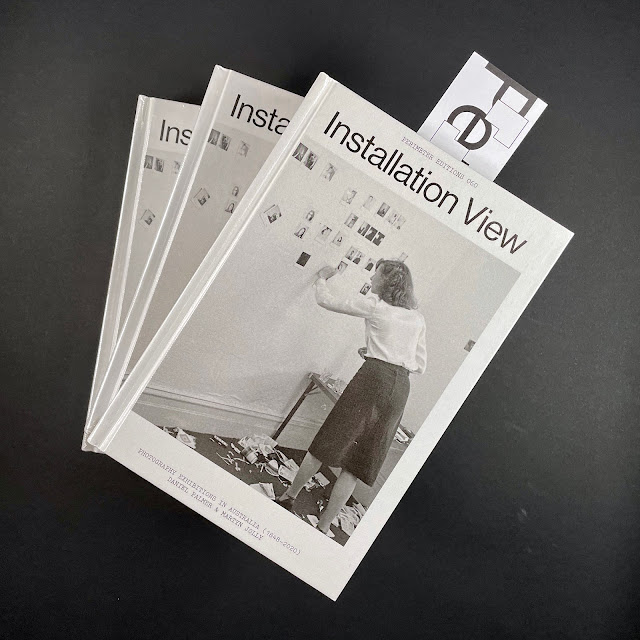

Daniel Palmer & Martyn Jolly| Installation View: Photography

Exhibitions in Australia (1848-2020)

In 2014, Canberra-based Dr Martyn Jolley and Melbourne-based Dr Daniel Palmer received a grant to research the impact of new technology on the curating of Australian art photography.

One outcome - their substantial new book, Installation View

- enriches our understanding of the diversity of Australian photography. It is a significant new account, told through the most

important exhibitions and modes of collection and display. It presents a

chronology of rarely seen installation views from both well-known and forgotten

exhibitions, along with a series of essays.

Additionally, the authors hope to identify some of the challenges faced by institutions in effectively engaging with new forms and practices of photography enabled through digital circulation. Establishing a dialogue around old and new curatorial approaches, the research is premised on the idea that in this age of photo sharing, when photographs are proliferating as never before, the curatorial selecting, collecting and contextualising functions have never been more important.

The foreword correctly notes that photos can be ephemeral even though the camera records and remembers. It invites readers to visit exhibitions of the past and actively imagine what it would have been like to be there. Somewhat like imagining what today’s virtual exhibitions might look like physically in an actual gallery.

1866_Intercolonial Exhibition_nla.obj-260430885-m

Our

appetites are whetted by references to viewing images at exhibitions, to the

ghostly figures that are audiences, and to the changes in exhibition spaces

since the 1870s - to spaces where photographers’ intentions interact with

institutional imperatives and exhibition design.

Then the introduction speaks of the exploration of the “constantly mutating forms and conventions through which photographers and curators have selected and presented photographs to the public”.

Despite the book’s 424 pages, the authors have had to be selective as to which exhibitions they have explored. I have also had to be selective as to which content to discuss here.

Seeking to demonstrate shifts in how photography has been conceptualised, who has produced it and the types of spaces where it has been exhibited, the authors note that photographers and curators have always grappled with scale so that images command attention. They discuss how photographs rely on other media, including print and reproduction technologies, and graphic design. They suggest that art museums have frequently turned to the nineteenth century to complicate the contemporary moment.

So, this is not a book for light reading. It is a substantial text to be studied, raising numerous things for us to consider and contemplate. I do not like the design – tiny margins, and a strange style of page and plate numbering – nor the lack of an index and the listing of the plates in the separate appendix. But the content is excellent. All serious creators, photographers and collectors should have a copy on their reference bookshelves.

An important question posed is what constitutes Australian photography? Is it work by Australians, here and on travels? Does it include significant works made by non-Australians whilst visiting these shores for short periods? How important are overseas exhibitions involving Australian-based photographers? Have exhibitions of international works here impacted on local practice? Very early in the book it is asserted that, in the 1980s, photography moved from the periphery to the centre of the art world; and it speaks about the loss of photo medium-specific curators and galleries.

Having personally had 45 years involvement with amateur Australian photography societies, I was enjoyed reading about the involvement of amateur associations and pictorialist photography exhibitions, starting with a description of the first annual exhibition by members of the Amateur Photographic Association of Victoria way back in 1884. Any person interested in photography would be aware of the New Zealand born, Sydney-based Harold Cazneaux. His 1909 solo exhibition in the Sydney rooms of the Photographic Society of NSW was the first such by any Australian.

Another

famous Australian, Frank Hurley, had his first solo show in 1911 – again in

Sydney, but at the Kodak Salon. Given our recent experiences of exhibitions

having to await gallery re-openings after pandemic lockdowns, it is interesting

that Hurley had to wait for the influenza epidemic to subside before his venue

similarly could re-open.

Reading about the use of photographers’ studios as exhibition spaces in the mid nineteenth century set me thinking about parallels today. Many photographers now would display examples of their works in their workplaces, including their homes, where clients would come to have studio portraits made.

Chapter 11, Exhibiting the Modern World, describes the major 1938 Commemorative Salon of Photography, again in Sydney, as part of the celebrations for Australia’s 150th anniversary. It was a joint effort by amateur and professional associations. Australia’s Bicentennial, 50 years later, is mentioned briefly in chapters about indigenous photographers and digital spaces, but the major 1988 traveling Australian Bicentennial Exhibition with which I was personally very involved is not discussed.

There is a reference to photographic constructions in the form of a ceremonial arch over Sydney’s Bridge Street during the 1954 Queen’s visit which I’m sure some will remember. The extraordinary and famous Family of Man international touring exhibition in 1959, including just two Australians out of 273 photographers, gets a short chapter to itself which refers to this country’s White Australia policy being dismantled against the context of the exhibition’s vision of global humanity.

1967_Expo '67 Montreal 2

1971_Frontiers, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne 8_RGB

The ongoing significance of some photography is highlighted by reference to the important After the Tent Embassy show – displayed at our own Woden shopping mall in 1983. It included some works that became incredibly important later.

Of considerable personal interest to me as an organiser of a current annual Prize for conceptual photography was the chapter Photoconceptualism, discussing the emergence of that style of exhibition practice. The first Australian exhibition to include conceptual photography was held in 1969 at Pinacotheca Gallery in St Kilda.

Juxtaposition of images and texts remains a device employed by many conceptual artists today. Locally, the Canberra PhotoConnect group aims to promote “the evolving practice of photography and its links to the arts and society”. It encourages using poetry as an integral part of image presentation.

Plates

in the book, of which there are 218, include a hand-coloured installation shot

of Micky Allan’s exhibition Photography, Drawing, Poetry – A Live-In Show.

Another has particular local interest, showing Huw Davies at the door of Photo

Access in Acton in 1984. The gallery at that organisation’s current premises

carries Davies name.

|

| 1978 Micky Allan, Photographs, Drawing, Poetry - A Live-In Show, hand-coloured installation shot, GPG, Melbourne, courtesy Helen Vivian |

References regarding Bill Henson, Simryn Gill, and Tracey Moffatt representing Australia at the Venice Biennale identify them as key moments putting Australia at the “centre of the art world”. The book also notes that photography has been “so successful at becoming art that the place of photography departments in Australian art galleries appears to have become unmoored”.

During an online conversation about the book, a question posed was whether institutionalisation has left us with sensory deficit. We heard that curators are now working like artists, and vice versa. Mention was made of William Yang using a gallery as a diary space. The audience, which included Yang, also heard that “each person who walks into a gallery changes everything”. Remember that when next you visit a gallery!