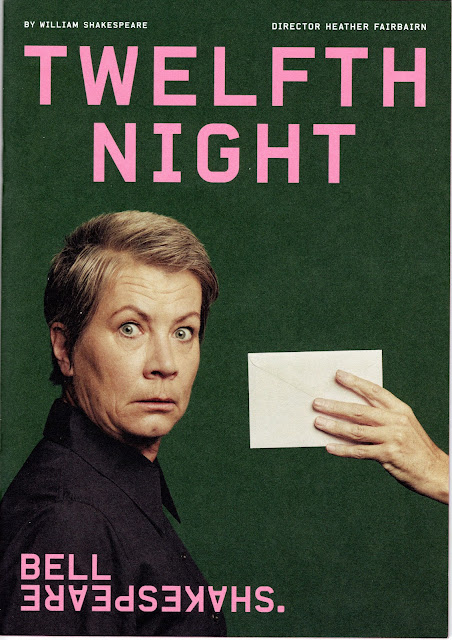

Twelfth Night; or What You Will by William Shakespeare. Bell Shakespeare at Canberra Theatre Centre Playhouse, October 13 – 21, 2023. Saturday at 1pm, 7pm; Sunday 4pm; Tuesday/Wednesday 6.30pm; Thursday/Friday 7pm; Saturday 1pm, 7pm.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

Opening Night, Canberra

Cast:

Malvolia – Jane Montgomery Griffiths Toby Belch – Keith Agius

Sebastian / Viola – Isabel Burton Viola – Alfie Gledhill

Maria – Amy Hack Orsino – Garth Holcombe

Andrew Aguecheek/Captain – Mike Howlett Feste – Tomáš Kantor

Antonio – Chrissy Mae Olivia – Ursula Mills

Creatives:

Director – Heather Fairbairn

Set & Costume Designer – Charles Davis Lighting Designer – Verity Hampson Composer – Sarah Blasko Sound Designer – David Bergman

Sound Associate – Daniel Herten Choreographer – Elle Evangelista

Voice Coach – Jack Starkey-Gill Fight & Intimacy Director – Nigel Poulton

|

| Mike Howlett (Andrew Aguecheek), Jane Montgomery Griffiths (Malvolia), Amy Hack (Maria) |

Bell Shakespeare have made the most exhilarating, imaginative, highly original interpretation of William Shakespeare’s most often performed play, Twelfth Night. Whatever else you have to do this week, make sure you don’t miss What You Will, and find out what Will really meant.

What he didn’t mean is the Canberra Times headline “The rom-com that never gets old” London, Christmas holidays 1600-01, population 200,000, was half the size of Canberra today but as politically aware as we are. The progressive Queen supported theatre arts while the 'no' voting Puritans did their best to shut theatres down. The story of the rich rabble-rousers Toby Belch and Andrew Aguecheek, via the incisive wit of the servant woman Maria, making such nasty fun of the puritanical Malvolio was chosen by Elizabeth and her Court for Christmas entertainment, rather than Ben Jonson’s satire of his theatre colleagues, The Poetaster.

Jonson was lampooning other playwrights but “he could not shove Will in with the rest of the poetasters. He was too big for easy lampooning. Moreover, Ben – as he acknowledged later in print – could not deny Will’s free and open nature, his lack of niggling jealousy. In spite of everything, they were friends.” Sounds a bit like what perhaps goes on off-stage among the many theatre groups in Canberra! (Shakespeare by Anthony Burgess: Jonathan Cape 1970 pp179-80).

And now, Bell’s director Heather Fairbairn has brilliantly taken Shakespeare an extra step forward in time. Making Malvolio into a woman, Malvolia, makes the comedy even funnier – very much in keeping with Will’s love of word play and sexual confusion – so we now have Viola, Olivia and Malvolia. There’s the ‘com’.

But Shakespeare’s ‘rom’ in this play was never sentimentally romantic, and as Fairbairn has pointed out, all parts were acted by men and boys (who were given special apprenticeship training to play women). The Poetaster was about these boys and women’s parts. Thomas Dekker attacked Ben Jonson back, with a play called Satiromastix, or The Untrussing of the Humorous Poet. This is the social context of William Shakespeare that Heather Fairbairn has understood – centuries before what we call naturalism on stage was invented by Henrik Ibsen (in A Doll’s House, 1879).

So the treatment of Malvolia, handcuffed and imprisoned in darkness, has a new unromantic meaning in our ‘MeToo’ world – about the far too common violence against women and the political issue of women’s empowerment. It’s both horrifying and powerful in the finale of Bell Shakespeare’s production to see Malvolia rise from the dark into the light. The audience on opening night cheered to see her resurrection. And applauded, in my view, one of the best Bell Shakespeare productions ever.

|

| Garth Holcombe (Orsino), Alfie Gledhill (Viola) |

|

| Mike Howlett (Andrew Aguecheek), Keith Agius (Toby Belch), Amy Hack (Maria) |

I say this because the originality in casting was wonderfully backed by an over-the-top style of acting, in absolutely extraordinary costumes, even more extravagant than Shakespeare himself could ever have imagined – but if he could be here in modern times he would surely be as enthusiastic about Charles Davis’ designs as the whole cast obviously are about performing in them.

As he would be too, about the characterisation of the Fool, Feste – the wildest philosopher, singer and disturber of our understanding of truth & falsity I have ever come across.

The amazing thing about this production is that there are so many angles of thought it generates – for us, as I’m sure it was for Will Shakespeare ‘celebrating’ Christmas (you’ll notice, by the way, that God never gets a mention in any of his plays – damned by the Puritans).

It’s not just about the stupidity of love (‘rom’) or the funny side of ruining other people’s reputations (‘com’), or the personal and political effects of women’s roles in a patriarchal society, but – via Feste and the entire impossibility of completely indistinguable brother/sister twins – even about the Donald Trumpian / social media post-truth world issues where conspiracies are taken to be real, logic need not be followed, and Me-Me is the only guideline.

Shakespeare understood this in the absurdity of the first lines by Duke Orsino, not so much in “If music be the food of love, play on” (though some have noted the whole play begins with an uncertainty in the word “If”), but in his demand:

“Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die.”

And if you want to go further, though Shakespeare wouldn’t have seen this before the industrial revolution, you can see today the result of such desire in the demand for ever increasing ‘economic productivity’, ‘profit-making’, and ‘development’ causing us to sicken and die from fossil fuel use and the resultant climate change.

|

| Ursula Mills (Olivia), Isabel Burton (Sebastian), Tomáš Kantor (Feste), Chrissy Mae (Antonio) Garth Holcombe (Orsino), Alfie Gledhill (Viola) |

And that’s not even mentioning the issue of war, which in Twelfth Night appears in the story of Antonio, the rescuer of Sebastian from the shipwreck which begins the play. He is afraid to go ashore because previously he had captained his ship in war against Illyria.

“I have many enemies in Orsino’s court,

Else would I very shortly see thee there.” (Act II, Scene 1)

And then, indeed, in Act III Scene 4, he is recognised:

Second Officer: Antonio, I arrest thee at the suit

Of Count Orsino.

Antonio: You do mistake me, sir

First Officer: No, sir, no jot: I know your favour well,

Though now you have no sea-cap on your head.

Take him away: he knows I know him well.

Antonio: I must obey.

[To Viola, who he mistakes for Sebastian]

This comes with seeking you;

But there’s no remedy: I shall answer it.

What will you do, now my necessity

Makes me to ask you for my purse? [which he had given to Sebastian]

It grieves me

Much more for what I cannot do for you

Than what befalls myself. You stand amazed;

But be of comfort.

Second Officer: Come, sir, away.

Antonio: I must entreat of you some of that money.

Viola: What money, sir? [She offers to lend him some, but Antonio thinks she is Sebastian refusing to give his money back]

They argue vociferously until the officers finally drag him away.

In the text, Act V, Scene I, when Antonio is under guard, and Sebastian and Viola appear at last together, there is no stage instruction. In Fairbairn’s production, Orsino quietly unlocks Antonio’s handcuffs; but despite his earlier explanation to Orsino how he had rescued Sebastian, but “I confess, on base and ground enough, Orsino’s enemy”, it seems to me that Shakespeare left him to be Orsino’s prisoner with no softening for his good deeds.

As Feste sings finally, Shakespeare was not under any illusions about reality. His Malvolio “hath been most notoriously abused” says Olivia, and the Duke orders “Pursue him, and entreat him to a peace”; but what peace can there be for Heather Fairbairn’s Malvolia? As little, I suspect, as for Will Shakespeare’s Antonio.

A great while ago the world begun,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain;

But that’s all one, our play is done,

And we’ll strive to please you every day.

I think Will means the simple truth is, however much you enjoy the Bell Shakespeare play as I did, that in the end, “The rain it raineth every day”.