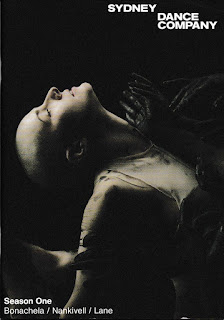

Season One 2019 – Bonachela / Nankivell / Lane. Sydney Dance Company:

Performed in this order:

Neon Aether choreographed by Gabrielle Nankivell

Music by Luke Smiles; Costume by Harriet Oxley; Lighting by Damien Cooper

Cinco choreographed by Rafael Bonachela

Music by Alberto Ginastera, String Quartet No.2 Op.26

Costume by Bianca Spender

Lighting by Damien Cooper

Woof choreographed by Melanie Lane

Music by Clark

Costume by Aleisa Jelbart

Lighting by Verity Hampson

Canberra Theatre Centre May 2 – 4, 2019.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

May 2

Since we are in election mode in Australia – compulsory preferential voting – I shall review in my order of preference, despite Season One’s title.

|

| Neon Aether Photo: Pedro Greig |

Nankivell’s Neon Aether is the best (indeed most wonderful and meaningful) of the three works on offer. Lane’s Woof is a special kind of satire – very effective. Bonachela’s Cinco – notwithstanding the terrific performance by the dancers – is disappointingly unimpressive.

So, in reverse order.

|

| Cinco Photo: Don Arnold |

A gentleman seated in front of me had been intently engaged throughout Neon Aether. But about half-way through Cinco, he decided it was necessary to re-tie a loose shoe lace, bending forward and sideways into the aisle – and blocking my view for at least a minute. When he straightened up, what I saw on stage looked more or less the same as before, as it had for most of the time before that, and continued to do afterwards.

Of course, the choreography of the individual moves was a ‘modern dance’ representation of changing relationships between the two men and three women – the five of the title – but as a work of theatrical art it was disappointing because there was no development, no drama with a beginning, middle and end.

When I read Bonachela’s Note in the program, I began to see why. “Using 5 dancers [because the music has five parts], I have explored the duality and opposition that I hear in the texture of the music….My approach to the work has been driven by a mathematical approach which” so he claims “has been wholly softened and enriched by my collaborators.”

I can certainly see the intention of Spender’s costumes and Cooper’s lighting, but the choreography is the problem. Ginastera’s String Quartet is an energetic description of the state of things, firstly in 1958 when he composed the work, but with an extra sense of how things were going wrong in his revision of 1968. It’s a powerful work, using strings to create an almost industrial musique concrète effect. It’s worrying from the beginning and ends with foreboding. But Bonachela’s response shows some minor ups and downs of mood with no particular state of feeling at the beginning, nor at the end.

All dance is mathematical – I’ve always been amazed at dancers’ capacity to keep to hugely complex counting systems which bamboozle me entirely – but the dance artist, the choreographer, must invest the mathematics with emotion and meaning for the audience. In Cinco I felt the dancer’s technical skills were all I had to engage me.

|

| Woof Photo: Pedro Greig |

In contrast, Woof was intriguing from the beginning. For so long nothing seemed to be happening except for freeze-frame photos between odd apparently random blackouts, as it the lighting system was playing up. Then bit by bit the movement speeded up, the freezes were overtaken by continuing change – and the choreography developed into what seemed to me to become a satire of modern dance itself. Soon there were a collection of characters on stage showing up all their pretentiousness, extending the satire off the stage. These characters, thinking themselves so full of importance, are us!

By now I was quietly laughing, foot-tapping along, and thinking am I really as bad as that? And how could this end?

As action got most absurd, the lights dimmed, the black cyclorama curtains parted to reveal a wonderful warm sunset glow, for the dancers to resolve into perfectly ordinary sensible people as they exited peacefully and cooperatively, the curtain closing behind them. A satirical ending? Perhaps, yet with positive feeling that we can get past pretention when artistry alerts us to the need for change.

|

| Neon Aether Photo: Pedro Greig |

Finally, Neon Aether presents us with a deeper sense of our place in the universe. I give it 5 stars. It’s an exciting, highly original and emotionally moving work. Where in Cinco the dancers could be seen to being ‘choreographed’ rather than dancing for themselves, and in Woof you could see the whole company working as a team to create their story, the dancers in Neon Aether seemed to have been given freedom to express themselves in a new way.

They were not ‘doing modern dance’ but each telling their own story of how impossible it is to understand how we fit into an unknowable universe. This work makes us understand that movement is everything and everything is moving – to forces which we may learn to manipulate in some small ways, but ultimately are far beyond our control.

The drama is played out through a single dancer – a woman in red who seems to represent Gabrielle Nankivell herself – who at times watches the actions of others, tries to become part of others’ action without ever being sure of her place, until she stands outside watching again in the second last scene, as she had done at the beginning. Then she is left alone on stage in a final terribly sad solo – alone on stage, alone in the world, alone in the universe.

All that freedom of expression, which is the core of great art, still takes us nowhere in the face of an uncomprehending universe. This work is the clear star of Sydney Dance Company’s Season One in 2019.

|

| Chloe Leong in Cinco Photo: Wendell Teodoro |