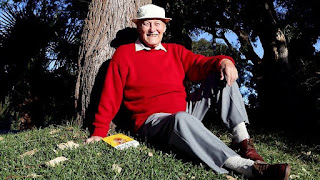

The late David Ireland.

THE great Australian novelist, David Ireland died one month ago on 26 July 2022 at the age of 94.

He won 3 Miles Franklin awards: in 1971 for ‘The Unknown Industrial Prisoner’, in 1976 for ‘The Glass Canoe’ and in 1979 for ‘A Woman of the Future’.

He was older than my parents and younger than my grandparents. We were friends.

I have written one fan letter in my life. It was late 2002. I was 35 years old. I wrote in green glitter gel pen.

Dear David Ireland, I think you are the greatest living Australian writer.

I can’t remember what else I wrote in the letter. Any drafts I made would have been destroyed on January 18 2003, when bushfires swept Canberra and my house burnt down.

A few weeks after the fires, I was at the bushfire recovery centre when my phone rang. He introduced himself and said he had to call me straight away because the letter had taken so long to reach him via his publisher and then his agent. He was sorry his reply was so delayed. He liked the green glitter gel ink. I said it was my daughter’s pen.

At least I think that’s how it went. Trauma clouds my memory of those post-fire years.

I had a school exercise book that I was using to write my life back into existence. I used a pencil to add David Ireland’s phone number and address to the growing list in the front few pages of the book. I said I would call him when I finished at the recovery centre. (I was about to write, when I was “home” from the recovery centre. But I didn’t really have a home. My children and I were in the midst of moving from my mother’s house to a hastily arranged rental.)

I first discovered him at Smith’s Alternative Bookshop in Canberra. It was summer holidays, possibly 1980. My friend and I were looking for a birthday present for my mother. My friend noticed this book, ‘A Woman of the Future’. She said that her own mother’s book club had recently been talking about it. It was David Ireland’s third Miles Franklin award winning novel.

We bought the book. My mother read it at least once and but I read it over and over. It was a disturbing, enticing and many-layered read. By the time it burnt, the spine had long-ago split into several pieces.

I was about 13 when I first read ‘A Woman of the Future’. Like Orwell’s ‘1984’, as I reread it over the next decade or so, I kept finding new meanings that I’d missed before. At university I studied Doris Lessing’s ‘Memoirs of a Survivor’ which, like Ireland’s book, is set in a dystopian time where wondering tribes are brought together by self-imposed exile. They remind me of the rag-tag anti-vaxxer, freedom protestors today.

Ireland’s novels are made of little vignettes. The scenes are evocative and sensory. in the early pages, they can seem random or unconnected. It’s better to let them wash over you than try to connect the dots.

About 2/3 of the way through the novel, it turns itself inside out and explodes with meaning and connection. Everything that has come before makes sense in unexpected ways. Then it picks up momentum, draws you helplessly along to the end, and leaves you heaving, like you’ve just escaped an undertow and been tossed by the shore-break onto the sand.

That gasping, heaving adrenaline-filled confusion pretty much describes how my two children and I existed in the dry, ashen weeks after the fires, when David Ireland first called.

It wasn’t so much losing everything as what we had seen, heard and felt.

A wave of flames roared across my front lawn toward me. I saw the washing on my line spontaneously combust. Dragons engulfed the bamboo and raced into my henhouse. The air was on fire.

And after, there was so much to do! It’s a strange thing to suddenly have to build a household out of nothing. Normally, it’s something that builds up over time.

The charity was overwhelming. But the labour of sorting through all the donated new and used clothes and household items was immense. I thought of myself as a super gatherer in the primal hunter-gatherer sense. I was in full survival mode.

I had been poised on the brink of self-actualisation. I had been about to release my first album the day after the fires. Now, in addition to the gathering, I needed to organise re-printing the CDs (because they had all burned) and negotiate a new launch, media strategy and distribution deal. For that I needed to go to Sydney, which is where David Ireland and I met.

He came in on the ferry to Circular Quay. He was tall and, as arranged, wearing a hat. It was soft and weathered, Akubra style.

I was wearing an embroidered waistcoat with little silver sequins. It was from one of those bags of donated clothes. I had described it to him as having little silver dots but he had heard it as silver clocks and so didn’t recognise me at first.

We went to one of those touristy places near the opera house and looking out toward the harbour bridge. We ordered lunch and a bottle of wine. I was drinking with the author of the darkly comic pub novel, ‘The Glass Canoe’.

We talked and talked for hours. I can’t remember much of what we said but I know it was animated and easy. After two (or possibly three) bottles, they refused to serve us any more wine and we wondered off into the city.

We were having fun. On an adventure.

Night was falling. In one pub, they said, we’ll serve you but not your dad. We slipped around the corner and shared my beer like naughty kids. We were thrown out of two pubs before the night was through.