|

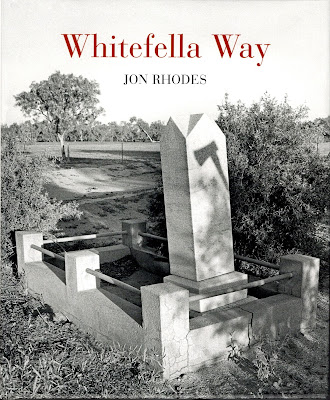

| Frederick Brooks grave, Yurrkuru or Brooks Soak, Coniston, Northern Territory |

Whitefella Way by Jon Rhodes. Published by Darkwood.

Format Hardback | 275 pages

Publication date 01 Sep 2022

Publisher Jon Rhodes

Publication City/Country Australia

ISBN10 064680202X

Reviewed by Frank McKone

|

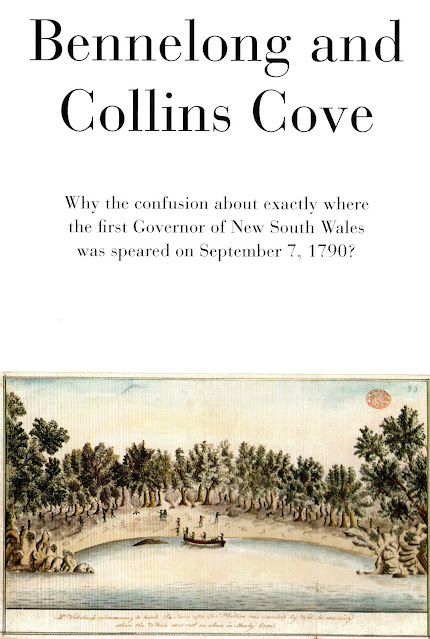

| Mr. Waterhouse endeavouring to break the Spear after Governor Phillip was wounded by Wil-le-me-ring (Port Jackson Painter, Collins Cove, circa 1790) |

Jon Rhodes is a creative recorder of the past in the present. In Whitefella Way he selects nine examples of points in time and place which document in words, paintings and photographs, a thread linking Blak and Whitefella cultural interaction 1788 to 2022.

This work is a development from his earlier highly acclaimed Cage of Ghosts (2019 Winner NSW Community and Regional History Prize) which followed his 2007 art photo exhibition of that title at the National Library of Australia. The central image which stimulated his social and artistic concern is of ancient rock art and graves enclosed in protective barriers with the intention of preventing damage and disrespect. He saw the irony of these cages for keeping ghosts safe.

Rhodes became interested in non-Indigenous people, amateur and professional archaeologists, who have recorded, for example, the rock engravings in the Sydney region. My experience working with bushwalking colleague, John Lough, around 1960, led to my providing a section of Chapter Five in Cage of Ghosts, about the question “Who spent 25 years tracing thousands of Eora and Dharug rock engravings at night, and what became of his hundreds of meticulously drawn surveys?”

Whitefella Way is laid out in a format similar to Cage of Ghosts, with each chapter followed by extensive numbered footnotes. Each chapter begins with a question, this time focussed on history connected to an artefact and its place.

Reading and looking at the artwork and photos is to read a story, of the past and often of the discovery of the past, to find the answer. Then the Endnotes fill in the details, often with surprising information – and provide you with a sense of the depth of historical research that Rhodes has undertaken; and with the sources which you may like to follow up according to your particular interests and concerns about the relationship between Australia’s oldest continuing culture on earth and the most recent problematical import.

Each chapter begins with a map, of Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) for Chapter One, where we ask the question about Bennelong and Collins Cove: “Why the confusion about exactly where the first Governor of New South Wales was speared on September 7, 1790?”

Examine the map, and you will find the spot in question: “Kay-yee-my Collins Cove 1788 Manly Cove”. Three names; two histories. And much more in the answer than I was ever taught in Year 9 Australian History.

Each chapter has its own focus question, and so can be read as a story and historical study in its own right. It seems a tenuous thread from one to the next, yet in the meaning of each answer, for both cultures, we come to understand what links the spearing of Capt Arthur Phillip to the simple but quite massive marble stone in front of the Australian War Memorial in the National Capital, Canberra:

THEIR NAME LIVETH FOR EVERMORE

Whitefella Way is intriguing to read – and crucially important to appreciate the need, now, for the truth-telling envisaged in the Uluru Statement from the Heart; especially from where I sit, in that National Capital, in Ngunnawal / Ngambri Country.

The publication is so up-to-date it makes “MY CHALLENGE TO Anthony Albanese” its forceful conclusion.

Not to be missed.

|

| Black’s grave near Pindari, Edward Thomson, circa 1848 |